Sea Shanties are work songs which were sung by sailors of the merchant service while at sea. In the Royal Navy, all orders were carried out in a man-o’-war in strict silence or to a fiddle or the pipe of the bo’sun’s whistle. In merchant vessels there was a standard format of shanty singing. One individual, the Shantyman, sang a solo line and the rest of the crew responded with another line, the chorus. One word of the chorus coincided with a vigorous simultaneous pull on a rope; the rhythms of the shanty co-ordinated the efforts of the sailors handling the ropes. This technique is well illustrated in the 1956 film “Moby Dick” where the crew of the Pecquod hoist the sails while singing “Blood Red Roses” – they haul on the words “Go down”. This was a hauling (halyard) or fore-sheet shanty sung usually when hoisting the sails. Windlass and capstan shanties were used for long repetitive tasks like weighing the anchor or pumping water from the bilges that required a sustained rhythm. Detachable capstan bars were positioned on the capstan drum and each crewman walked behind the bar and by pushing made the drum revolve in a clockwise direction – and the anchor, attached by a rope or cable to the drum, was raised. Unlike the hauling of halyard shanties, this was a continuous motion.

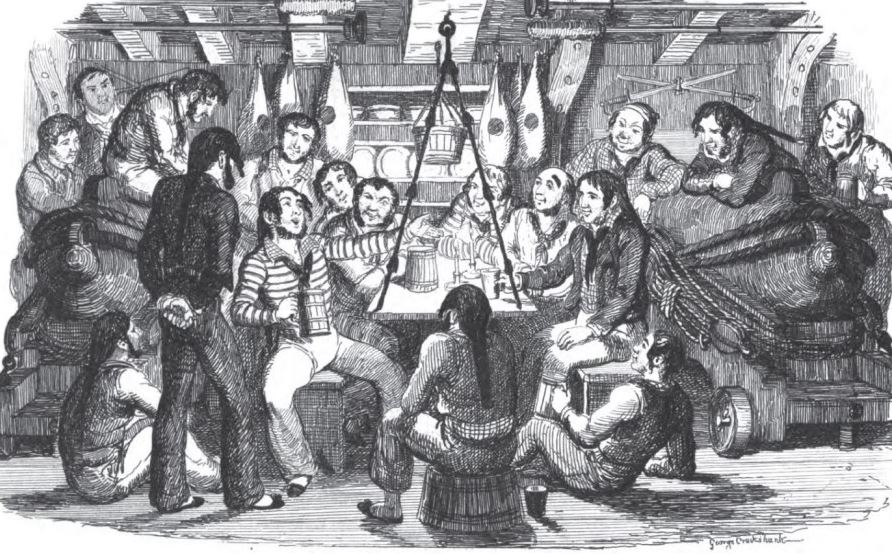

The crew’s quarters were housed in the forecastle, a deckhouse towards the front of the ship, and that was where seamen spent most of what little leisure time they had. Occasionally they would sing songs there which were not working shanties. They chronicled famous battles and heroes, places they had visited, romance and their great longing to sail home. These songs were known as fore-castle shanties or fore-bitters.

Work songs in ships developed over hundreds, or even thousands of years. There is evidence that galley-slaves in Greek triremes and then in Roman quinqueremes chanted as they rowed. Some of the more modern shanties can be traced back to Tudor times. “A-Rovin’ ” (or “The Maid of Amsterdam”) is a popular present-day song but it is said to have been sung in Elizabethan times. The golden age of sea shanties was the early and mid-19th Century and the sources of these songs were numerous. Most shanties developed in Britain, the United States or in Northern Europe. Although a particular shanty may be sung in a number of countries, the lyrics are often very variable. These songs invariably contained very rough language, much misogyny and there was little racial tolerance. A rigid taboo prevented them from being sung ashore. Songs performed by modern-day shanty groups have usually been cleaned up.

There are a number important books on sea shanties. “The Shanty Book” was written in 1921 by a Northumbrian, Richard Runciman Terry, who was a well-known classical musician and composer and who was related to Sir Charles Runciman, a ship owner and shipping magnate. This book was a departure from his interest in church music but it gave an excellent insight into the shanty as the sailor’s work song. The author acknowledged, however, that the time of the sea shanty was over. The modern shantyman’s bible is “Shanties from the Seven Seas”. This 428 page tome which contained about 400 sea shanties, was written by Stan Hugill, who was started his working life in Merchant Navy steam ships in 1921 and later sailed in square-riggers. He was encouraged in this literary endeavour by Dr Kurt Hahn, who was the Headmaster of Gordonstoun School. This was the alma mater of the Duke of Edinburgh and the Prince of Wales and seamanship was an important part of the school’s curriculum. Hahn was concerned that shanty singing was dying and was convinced that it was important that the sea shanties genre should be perpetuated. He persuaded Hugill, who was inactive at the time because of a foot injury, to research shanties and to record his findings. Stan Hugill’s opus magnum was the result.

In the second half of the 19th Century, the steam winch and the donkey engine replaced the manually-operated capstan and windlass and there were very few physical tasks on vessels that had to be performed by hand. The coming of the screw-engined steamers obviated the need to hoist sails and this brought about the demise of traditional sailing ships and sounded the death-knell of the sea shanty.